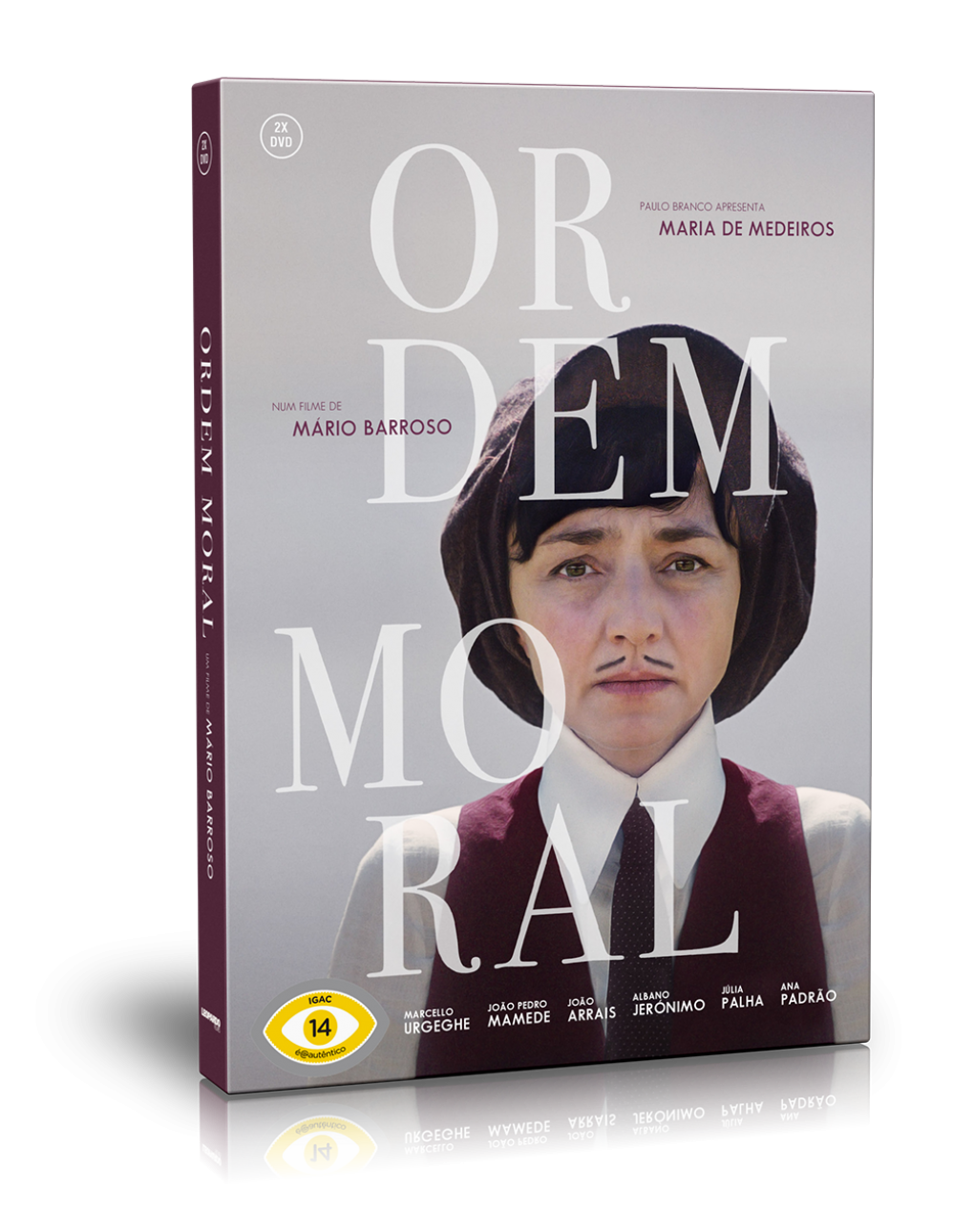

Moral Order Ordem Moral

In 1918, Maria Adelaide Coelho, heiress and owner of the newspaper Diário de Notícias, abandoned the social, cultural and family luxury in which she lives to escape with an insignificant chauffeur, 26 years younger. The consequences of this decision will obviously be painful and morally devastating…

Special Edition with 2 Discs (digipack):

Disc 1— Film (101'); Audio Dolby Digital 5.1

Disc 2 — Bonnus + TV-series (116'); Audio Dolby Digital 2.0

Video: 16X9 | 2.00:1 | Color | DVD9

Bonus material of the video edition

TV-Series + Bonnus:

- TV-Series (3 Episodes)

- Interview with Mário Barroso and Paulo Branco

- Trailer

Festivals and awards

33 Tokyo International Film Festival (Japan) - Tokyo Premiere

35 Mostra de Valencia - Cinema del Mediterrani (Spain) - In Competition

43 Mostra Internacional de Cinema - São Paulo International Film Festival (Brazil)

Ariel Awards 2021 (Mexico) - Representative of Portugal in the category of Best Ibero-american Film

IFFI - International Film Festival of India 2021 (Goa) - Official Selection

Sophia Awards 2021:

Best Score – Mário Laginha

Best Hair and Make-up – Ana Lorena, Natália Bogalho

GDA Foundation Actors Awards – Maria de Medeiros, Best Lead Actress Award

Reviews

««Mário Barroso quis contar a história da mulher que queria ser livre»»

««Ordem Moral – que papelão maravilhoso!»»

««Mais do que escolher, somos escolhidos»»

««A madame, o motorista, os alienistas e o marido dela»»

««Os homens e as mulheres têm de ser feministas, como ser antifascistas»»

««O amor (não) é coisa de loucos»»

««A fuga de uma vida de luxo na luta pelo amor»»

««Nada de misericórdia!»»

«"True and romantic, the story of Mário Barroso's film is brought to light by the fusion of mise en scène and the acting by its lead actress."»

«"Elegant and classic, the film offers Maria de Medeiros the opportunity for a very beautiful performance, in a vibrant and melancholy tribute to a sweet rebel."»

«“Maria Adelaide Coelho da Cunha is a pioneer of European feminism, as this beautiful film by Mário Barroso demonstrates."»

Cast and crew

Maria de Medeiros

Marcello Urgeghe

João Pedro Mamede

João Arrais

Albano Jerónimo

Júlia Palha

Ana Padrão

Vera Moura

Dinarte Branco

Ana Bustorff

Rita Martins

Miguel Borges

Sonia Balacó

Jorge Mota

With the special participation of

Isabel Ruth

Rui Morisson

Teresa Madruga

Screenplay and dialogues Carlos Saboga

Direction and photography Mário Barroso

Original music Mário Laginha

Set design Paula Szabo

Costumes Lucha d’Orey

Sound Ricardo Leal, Pedro Góis

Editor and Assistant Director Paulo Mil Homens

Executive producer Ana Pinhão Moura

Poducer Paulo Branco

A Leopardo Filmes production

In association with APM Produções

With the financial support of

Instituto do Cinema e do Audiovisual

Ministério da Cultura

Fundo de Apoio ao Turismo e ao Cinema

Rádio e Televisão de Portugal

Câmara Municipal de Lisboa

Lisboa Film Commission

Cofina Media S.A.

With the support of the Creative Europe Programme - MEDIA of the European Union

Portuguese distribution: Leopardo Filmes

International sales & festivals: Alfama Films

Director's biography

Mário Barroso was born in 1947 in Lisbon, where he completed high school. Then, he studied Theatre and Directing at INSAS, in Brussels. In 1976 he graduated, with honors, with a degree in Directing and Image from I.D.H.E.C. - Institut Des Hautes Etudes Cinématographiques, where years later he became a lecturer.

Alongside his passion for film, he worked as translator and host of the show “Les grands moments de la musique française” (1970/74), journalist, producer at R.F.I, and correspondent for the daily Portuguese newspaper República (1970/74) in Paris.

With over four decades of his career devoted to the seventh art, he also participated as an actor in Francisca (1981), O Dia do Desespero / The Day of Despair (1992), and O Velho do Restelo (2014), by Manoel de Oliveira.

He is considered one of the best and most acclaimed Portuguese cinematographers, having worked with renowned directors like Manoel de Oliveira, João César Monteiro, Raoul Ruiz, José Fonseca e Costa, and Jean-Claude Biette, among others.

He has directed short films, documentaries, television shows, television films, and three feature films: O Milagre Segundo Salomé / The Miracle According to Salomé (2004), an adaptation of the homonymous novel by José Rodrigues Miguéis that was extraordinarily well received by critics and the general public; Um Amor de Perdição / Doomed Love (2009), which was selected in various international film festivals; and, now, Ordem Moral / Moral Order (2020).

Intentions note

This project arises from a desire: to film an actress. The expressions of an actress. The look of an actress. The face, the hands, the skin of an actress. The body, especially the body of an actress. The actress Maria de Medeiros.

More than an intention, there is this fact. I have been a director of photography for about 40 years. I have spent my life filming and lighting actors and actresses, sets, animals, cutaway shots and silly things. I know what I don’t want. I have consideration and respect for TV movies, I consider the stories to be effectively told, as proof of a rare talent.

But in this project of mine I would like the story we are going to tell not to restrain my imagination. I will ensure that it will serve us as a pretext to invent images, sounds, feelings.

It is in Maria Adelaide’s face that I would like to find the receptacle of our fears, our indignations and our wishes. More than the story that we tell through her, there will always be the skin texture, the light that abandons her, the desire that consumes her, the body that withers away, that hand that shakes in tenderness, the insane look.

Mário Barroso

Interview with Mário Barroso

How were you introduced to the figure of Maria Adelaide Cunha Coelho?

I had a second degree uncle, who lived on our street and who we used to call “uncle-colonel” – who was sub-director of the Diário de Notícias newspaper in the 50s. I was a kid and liked him because he told us a lot of stories, always with a lot of humor in the mix (he also wrote revues). I was around 10 or 11 years old when one of the stories that my uncle – his name was Pereira Coelho – told me was about the newspaper’s former owner, who had run away with her driver. A rich woman who at almost 50 years old decides to run away with her much younger driver was something unheard of, and I remember finding her very brave.

Some years ago, while brainstorming for a new film, I remembered that story – also because I really wanted to film with Maria de Medeiros. And, after beginning to work on it and further investigating this woman’s story, that was initially told to me by my uncle (above all, I wanted to tell it in a way that wasn’t conditioned to my imagination) – I became increasingly convinced that Maria would have to play this role.

That means that while writing the script, you already had Maria de Medeiros in mind?

Yes, yes. She was the only Portuguese actress who was adaptable to my vision of Maria Adelaide, who corresponded precisely to what I thought, after everything I had investigated and read. Beyond her enormous talent, she possesses an odd beauty, exotic, different, that has nothing to do with traditional beauty. It’s something that begins with her facial expression.

I had decided that I didn’t exactly want to tell a story of ravaged love, such that everything that happened was the result of great passion. What fascinated me was that strong woman, who fought and won, who had the courage to abandon a family and material comfort, and run away. In fact, she was a free woman, a woman who fought for her desire to live out her freedom. Who decided to choose her life, which at the time was extremely difficult, as it turned out to be. And it was in that sense that Carlos Saboga and I developed the screenplay.

What about the rest of the cast, which is exceptional and functions like a well-oiled machine?

It was gradually chosen from then on, after Maria. A husband who was the same age and had a good figure (Marcello Urgeghe, whom I’ve known since he was a kid, and whose irony I exploited in his performance). For the driver, João Pedro Mamede. The friend from the syndicate is Albano Jerónimo, who I had seen in The Domain, and who is fantastic. Dinarte, who I’ve also known for many years, is Egas Moniz. João Arrais is the son. Maria Adelaide’s friends are all great actresses, like Ana Padrão, and also, from a younger generation, Júlia Palha. There are still special participations from Isabel Ruth, Teresa Madruga, and Rui Morrison. I tried to exploit each person’s characteristics, as best as I could.

And you also play a small role, with a curious name, might we add?

Oh, that’s just for kidding around… I was a “guest actor” in many films, including [João] César Monteiro’s. We didn’t have anyone to play that minor role, and I decided to do it myself, and, as an homage to César Monteiro, to use the same name [Dr. Cruel, in God’s Comedy, 1995]. Only, by mistake, I mistook his first name and only realized that later. In César Monteiro’s film I was Dr. Pedro Cruel and here I am Dr. Aníbal Cruel [laughter].

Other notable things in the film are the set and set design, which are fundamental in rebuilding the time period…

We got really lucky that we were able to film in the Veva de Lima house, a fantastic house that hosted literary evenings in Lisbon in the 20s and 30s. It was what I was looking for. And so we were able to recreate that theatre. Maria Adelaide had a great passion for theatre and organized those performances. In the film I have her direct two plays. In her house in Lisbon, Sóror Mariana [about Mariana Alcoforado, the nun of the Letters of a Portuguese Nun] by Júlio Dantas, which was very fit to the situation and reinforced the film’s plot (and Dantas was, in fact, a family friend); then, in the hospice, Miss Julie, by Strindberg, which inverts the situations, of genre and class, where she plays the servant.

The movement of Maria Adelaide and her hair, in the opening and closing of the film, likewise reminds us of the theatre.

Yes, there is from the start a strong notion of acting and the theatre is a through line in the film. Maria Adelaide is also an actress and there’s that side of acting, a sort of “falseness”, of “pretence” (and, curiously, on her end, it’s a bit like Fernando Pessoa’s line: she “pretends so completely, she even pretends to pain the pain [she] really feels”).

And it’s starting then that Egas Moniz makes his diagnosis?

I didn’t want that the idea of a complot were too pronounced. Today we live times that favor the complot, where everything is contrived. It’s obvious that her husband, Alfredo da Cunha, utilizes the power he has, but the diagnosis by Egas Moniz, Júlio de Matos, and Sobral Cid – who were the higher ups in psychiatry at the time – was, when we think about it, a diagnosis that corresponded exactly to the thinking and medical practices of that time period. In the film, there isn’t a single quote from Egas Moniz that wasn’t taken from his writing. That was what the alienists of the time understood about women. Which came in very handy for Alfredo da Cunha. To him and to their son, Maria Adelaide’s escape was an enormous humiliation. And the way they found to overcome that was by declaring her insane. And within a certain conservativism, those doctors were in fact convinced that the woman was crazy.

Hence the title Moral Order.

Precisely. A title that began as provisional and that I didn’t want to stay…

Why?

Because it seemed a bit pretentious to me [laughter]. Not a lot of people know what the moral order is. During that time the republicans spoke of the Republican Order while the monarchs, conservatives and church spoke of the Moral Order. The two opposed each other. And Maria Adelaide was questioning the later.

Maria Adelaide’s story relates a bit to Salomé’s story in The Miracle According to Salomé, your first feature. Is it a principle of feminine autonomy that precedes your interest in these characters?

Yes, a feminine autonomy, similar in both films – and, by the way, also in Doomed Love [2008] –, which I consider more rational than passionate. Because I think that passion ends up having an aspect of subjection; a person is dominated by their feelings. In all of these cases there is a will that goes beyond passion and seeks to break with what there already is, with what’s instituted. For that reason, the end of Maria Adelaide’s story – one that recounts someone who spent days embroidering curtains after that emancipatory gesture – I was no longer interested in depicting.

One detail of the film’s “choreography” is the recurring motion up and down flights of stairs, which you seem to film with some emphasis. Can we relate that movement with the protagonist’s easy circulation between high society and poorer environments?

I hadn’t thought of that. It’s one of those unconscious things that a director does. But there is, in fact, a permanent social climb and descent. And those stairs also have a theatrical side. As I said, we’re always facing the representation of something.

The action of journalism as a backdrop already existed in The Miracle According to Salomé and it’s once again present in the same way in Moral Order. Is it a coincidence or are you interested in journalism as a “character” (not necessarily in the form of a journalist)?

Well, a coincidence I’ve already been asked about meanwhile is if there already was covid-19 when we made the film…

Because of the sequence that shows people who were sick with the Spanish Flu [the 1918 Flu pandemic] …

There was no Covid-19 when we shot, that’s for sure, a situation like that didn’t even cross our minds; but they’re images that come up in a moment that might allow us to better understand what a pandemic was at that time. Now in regards to the newspapers, I’ve always had an enormous respect for journalists, having grown up in a dictatorial country… Before completing cinema school, I worked at RFI – Radio France Internationale – for some years, and, although I wasn’t a serious journalist, it’s one of the professions that I’m most fascinated by. Hence the reason why the story of the sale of the newspaper moves me. Let’s see, when the Diário de Notícias was sold, it ended up becoming one of the bases of support for the coup on May 28th [1926] and for the New State (the dictatorship of Estado Novo) that followed.

How do you reconcile the work of a director with that of a cinematographer in the film?

For me, that’s the easiest thing to manage. Because I know exactly what to do, how I’m going to film. When I get to the set, I don’t even have 3 minutes of hesitation. I work on the set design with the set designers, on the wardrobe with the costume designers (and let me highlight that in this film the work by Paula Szabo and Lucha D’Orey is magnificent), but when I get to the set I know what I have to do perfectly, the place where to put the actors in order to best utilize the presence and absence of light. That especially facilitates my work. In this film I utilized natural light primarily, and sometimes I’d reinforce it in one place or another, but that never caused any difficulty, since I always was perfectly aware of how to do it. I can even say that there are many aspects of mise en scène in the film that are a result of my vision as cinematographer, and of a certain “effectiveness” related with the short amount of time that we have while shooting.

And the musical score was done by Mário Laginha.

Mário had already worked with me on a documentary. And it had gone really well. I really like his work and I’m very fond of him. My previous films had music by Bernardo Sassetti, whom Mário was friends with and had worked together with. I thought he’d be the ideal person to score the film. And he was.

Moral Order comes 10 years after your previous film, Doomed Love [2008]. Why so long without directing?

I’m going to answer you by going back to the beginning of everything… at IDHEC (Institut Des Hautes Etudes Cinématographiques), where I graduated from, there were two possible specializations: editing or cinematography. I chose the later, and at the beginning there was that idea that we were a bit like wizards with the film, the light, etc. I was taken by that fascination, and I entered a certain rhythm of work as a cinematographer, which was how I made a living, and I only started making films as a director when I no longer needed to make a living. So, I make these films out of genuine pleasure, without any temporal discipline.

And even though you live in France, you still shoot in Portuguese…

Thinking of that, it’s curious that nowadays I dream more in French than in Portuguese… But I love Portuguese. And, more than cinema itself, going back to the matter of the charm of theatre, my memory is in Portuguese, from the start, because of my aunt, the actress Maria Barroso, whom I greatly admired. When I was a kid I wanted to be a theatre actor.

Inês N. Lourenço and A. M. C.

Special Edition with 2 Discs (digipack):

Disc 1— Film (101'); Audio Dolby Digital 5.1

Disc 2 — Bonnus + TV-series (116'); Audio Dolby Digital 2.0

Video: 16X9 | 2.00:1 | Color | DVD9